"But I say to you, Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be children of your Father in heaven." - Matthew 5:44-45

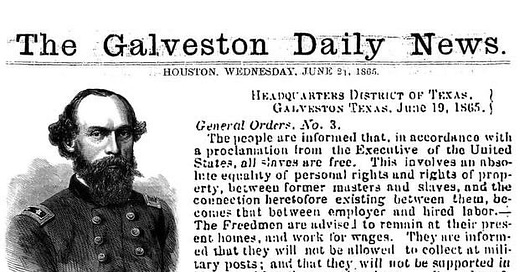

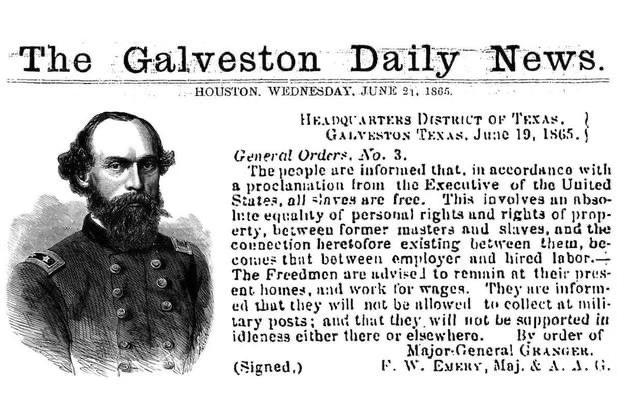

On June 19, 1865, Union troops arrived in Galveston, Texas, with news that should have transformed the American church: enslaved people were free. The Emancipation Proclamation had been signed two and a half years earlier, but word had been deliberately withheld. When freedom finally came, it arrived not through the prophetic voice of the church but through the force of federal troops.

This delay—and the church's complicity in it—reveals a pattern that continues to haunt American Christianity today. Just as news of freedom was suppressed in Texas, the gospel's multiethnic vision has been consistently resisted, diluted, or ignored by much of white American Christianity. Juneteenth confronts us with an uncomfortable truth: we have often been antagonists to God's inclusive kingdom rather than allies of His reconciling work.

I have the honor of consulting with churches attempting multiethnic ministry and have repeatedly seen this pattern. Many white Christian leaders approach diversity work with the same mentality that delayed news of emancipation—we control the timeline, we determine the terms, and we maintain the power to decide when and how change happens. This approach isn't just ineffective; it's antithetical to the gospel we claim to believe.

But here's what gives me hope: the same gospel that demanded emancipation in 1865 demands authentic multiethnic community today. The adaptive resilience that carried our brothers and sisters through systemic oppression can now guide us toward institutional transformation.

What We Knew But Wouldn't Preach

The early church faced their own "Juneteenth moment" in Acts 15. Jewish believers had received earth-shaking news: God was extending salvation to the Gentiles. But like slaveholders who withheld news of emancipation, some Jewish Christians resisted this expansion of God's kingdom. They developed theological arguments for why Gentiles needed to become culturally Jewish before they could become authentically Christian.

Sound familiar?

The Jerusalem Council's resolution wasn't just about circumcision—it was about whether the gospel creates one multiethnic church or multiple mono-ethnic churches that happen to believe the same doctrines. James's wisdom in Acts 15:19-20 established a principle that should guide us today: we must distinguish between essential gospel truths and cultural applications of those truths.

But Acts 15 is just the beginning. The entire New Testament assumes a multiethnic church. When Philip encounters the Ethiopian eunuch in Acts 8, Luke doesn't present this as an unusual occurrence requiring special explanation—it's the natural outworking of a gospel that transcends ethnic boundaries. When Paul plants churches throughout the Mediterranean, he consistently creates communities where Jews and Gentiles worship, serve, and lead together.

Paul's letters constantly address the tension between Jewish and Gentile believers, not as a problem to be solved but as a reality to be navigated with wisdom and grace. Ephesians 2:11-22 declares that Christ has "broken down the dividing wall of hostility" between ethnicities. Galatians 3:28 proclaims that in Christ "there is neither Jew nor Greek." Revelation 7:9 envisions worship "from every nation, from all tribes and peoples and languages."

This isn't optional theology. A gospel that doesn't encourage multiethnic community isn't the whole gospel. A church that remains ethnically segregated, by choice rather than circumstance, has not fully embraced the reconciling work of Christ.

Yet American Christianity has spent centuries developing theological arguments for why this biblical vision doesn't apply to us. We've created sophisticated justifications for homogeneous churches, just as antebellum Christians created sophisticated justifications for slavery. Both represent the same fundamental error: subordinating God's inclusive kingdom to our cultural comfort.

The technical competence gap among white church leaders regarding this biblical foundation is staggering. Most of us can't articulate a biblical theology of diversity beyond generic statements about loving our neighbors. We're unfamiliar with how the multiethnic trajectory runs from Abraham's calling to bless "all nations" through the early church's inclusion of Gentiles to Revelation's vision of diverse worship. We lack frameworks for distinguishing between cultural preferences and biblical principles.

How Freedom Was Delayed Again and Again

The period following Juneteenth reveals how quickly good intentions can be undermined by systemic resistance. During Reconstruction, churches experienced genuine integration. Former slaves and former masters worshiped, served, and led together. For a brief moment, it seemed like the American church might embrace its multiethnic calling.

But by 1890, most denominations had become more segregated than before the Civil War. The same Christians who had celebrated emancipation created new systems to maintain racial separation. They didn't all reject multiethnic ministry theologically—they simply found practical reasons why it couldn't work in their particular context.

This pattern has repeated throughout American church history. The Azusa Street Revival of 1906 began as a radically integrated movement where "the color line was washed away in the blood." William Seymour, a Black preacher, led a movement that attracted people across racial lines who experienced the baptism of the Holy Spirit together. But within a decade, most Pentecostal denominations had segregated along racial lines. White leaders couldn't tolerate Black authority, even when spiritual gifts had validated that authority.

The Civil Rights movement found its most vigorous opposition not from secular institutions but from white churches that claimed biblical authority for racial separation. Denominational leaders crafted theological arguments for segregation that would have made antebellum theologians proud. They quoted Scripture about the "curse of Ham," emphasized the "different but equal" nature of racial groups, and insisted that integration would lead to moral compromise.

The pattern was the same each time: initial enthusiasm for biblical ideals, followed by practical resistance when those ideals threatened existing power structures, followed by theological justification for maintaining the status quo.

Today, Sunday morning remains the most segregated hour in America. Despite decades of racial reconciliation rhetoric, church attendance patterns have barely changed. We've had countless conversations about diversity, but seen minimal transformation in our institutional structures.

Why does this pattern persist? Because we've approached multiethnic ministry as a program to implement rather than a gospel truth to embody. We've treated it as an addition to our existing church model rather than a reformation of our understanding of what the church is supposed to be.

The Uncomfortable Truth About Church Today

Last year, I was consulting with a church that had hired its first Black associate pastor. The senior pastor, a well-meaning man who had preached about racial reconciliation, called me because they were experiencing "unexpected tensions." During our conversation, he mentioned that they had restructured the associate pastor's role three times in eighteen months, each time reducing his responsibilities.

"We want him to succeed," the senior pastor insisted. "We just need to find the right fit."

As I dug deeper, a pattern emerged. Every time the associate pastor proposed changes that reflected his cultural perspective—whether in worship style, leadership development, or community engagement—he was told those changes "didn't align with our church culture." When he raised concerns about the lack of diversity in their elder board, he was counseled about "maintaining unity." When he suggested partnerships with Black churches in their community, he was reminded about "staying focused on our mission."

This church wasn't actively racist. They genuinely wanted diversity. But they wanted diversity that required no change from them. They wanted the benefits of multiethnic ministry without the discomfort of multiethnic transformation.

This is the current reality for most white churches pursuing diversity: we're unconsciously requiring people of color to adapt to our cultural norms while maintaining the illusion that we're creating an inclusive community. We're like the Galveston slaveholders who celebrated emancipation while developing new systems to maintain control.

The institutional incompetence goes deeper than individual prejudice. Too many white church leaders lack basic knowledge about how systemic racism operates in church contexts. We've never seriously studied the theological foundations of multiethnic ministry. We're unfamiliar with church history's racial dynamics. We don't understand how our cultural assumptions shape everything from worship design to decision-making processes to conflict resolution.

Too many of us attempt to lead multiethnic communities without the theological, historical, or practical knowledge necessary for the task. It's like attempting surgery without medical training—good intentions aren't enough when technical competence is required.

Your Next Right Thing

As we observe Juneteenth this year, the first step toward authentic multiethnic ministry is taking stock of our current reality. This means asking uncomfortable questions about our churches, our denominations, and ourselves:

Where have we been complicit in delaying the gospel's multiethnic vision? How have we used theology to justify cultural comfort? What systems in our churches require people of color to adapt rather than creating space for mutual transformation?

This kind of honest assessment requires "adaptive resilience"—the capacity to face difficult truths without becoming defensive or despairing. It means acknowledging that our resistance to multiethnic ministry isn't accidental or anomalous—it's part of a historical pattern that dates back to the earliest attempts at church integration.

But assessment alone isn't enough. Tomorrow, in Part 2 of this series, we'll explore what genuine multiethnic ministry looks like when rooted in biblical vision rather than cultural accommodation. We'll examine the difference between diversity programs and gospel transformation.

The news of freedom has been proclaimed in Scripture for two thousand years. The question is whether we'll continue to delay its implementation or finally allow it to transform our churches into the multiethnic communities that so clearly display the kingdom of God.

Tomorrow: Part 2 - "The Vision We Fear: What Authentic Multiethnic Ministry Actually Looks Like"